Understanding the Crisis of Democracy in West Africa and the Sahel

There have been several coup d’états in West Africa and the Sahel in recent years, raising concerns about the future of democracy. The question is, why is democracy in crisis and military regimes on the rise in these regions? This article briefly explores some key issues affecting these processes.

There has been a sustained threat to democracy in West Africa and the Sahel in the last few years. Seven coup d’états have occurred in these regions since 2020, four of which were successful, with the coup in Niger in July 2023 being the most recent, following those in Guinea, Burkina Faso, and Mali. (There was also a successful coup in Gabon, but it lies outside the regions that are the subject of this paper.) In all four cases the official reasons given by the military juntas for their decisions to overthrow the democratically elected governments were similar: economic stagnation and persistent insecurity. One other key trend is that the coups were positively received by large sections of the public in all four countries. This article explores the reasons for these coups and public responses to them.

Insecurity in West Africa and the Sahel

The four countries in question are among the ten countries with the lowest Human Development Index scores. Countries such as these are faced with widespread poverty, poor education, lack of adequate health care and, perhaps most importantly, unstable governments. International Monetary Fund reports show that these countries also have some of the lowest annual rates of GDP per capita in the world. Apart from Guinea, which has an annual GDP per capita of US$1,500, the figure for each of the other three countries is less than US$1,000 a year?

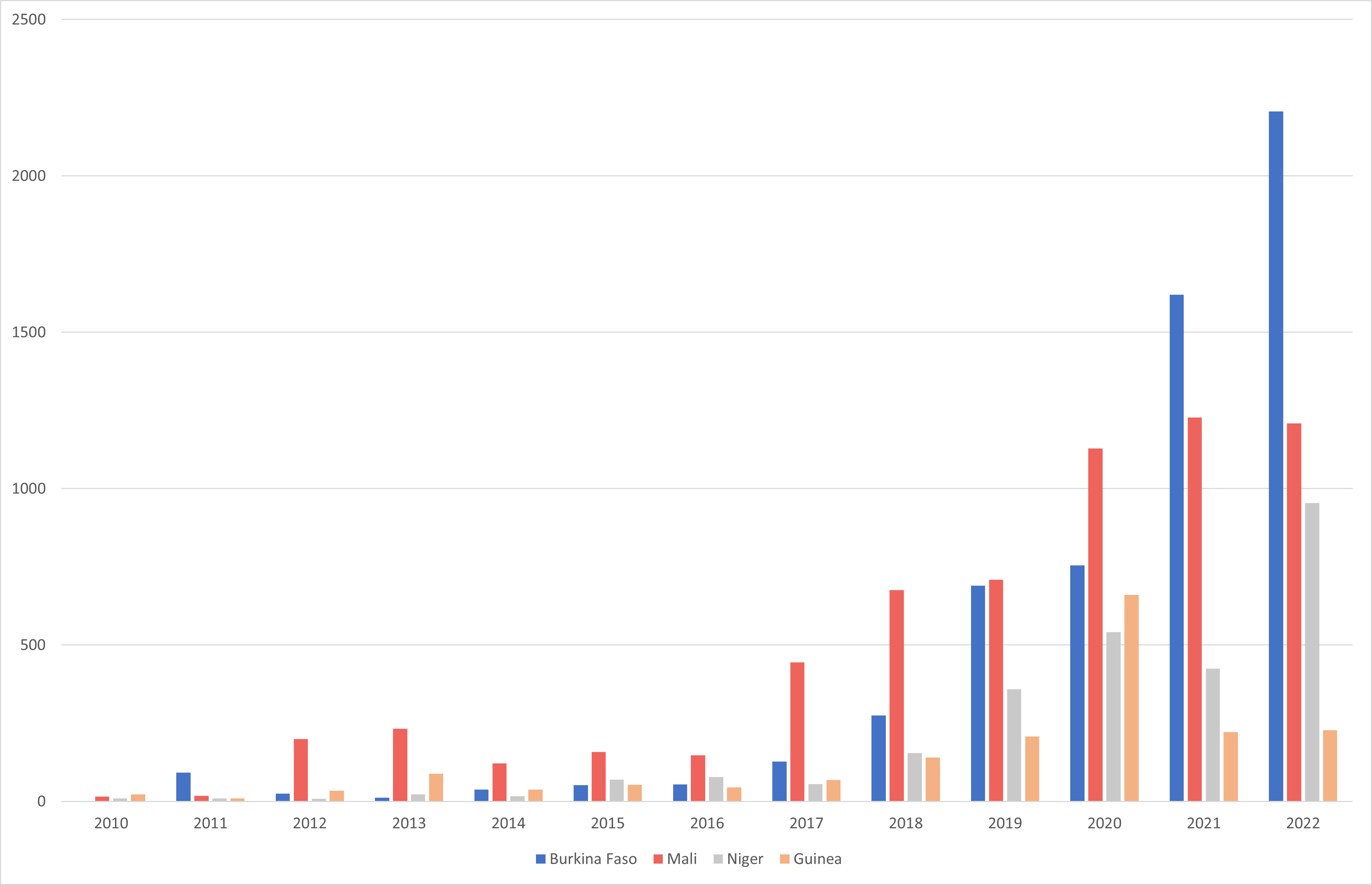

Figure 1 shows the number of violent attacks in the four countries between 2010 and 2022. This indicates that insecurity has risen in all four countries, justifying the claims of the military juntas that insecurity has increased and civilian regimes are unable to ensure security, and combat insurgency in particular. In total, Burkina Faso has been experiencing the highest number of insurgency-related violent incidents, followed by Mali and Niger. In Guinea, on the other hand, the rise in insecurity is mostly due to communal violence, and the main reason given by the military for the coup in that country is political maladministration. Insecurity rather than poverty plays a significant role in motivating the coups in these regions because other Francophone countries such as Togo, Mauritania and Benin are poverty-stricken, but have not experienced the same levels of insecurity as the four that have experienced military takeovers, and have relatively stable democratic governments.

Figure 1: Violent attacks in Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger and Guinea, 2010-2022

Source: Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED): <https://acleddata.com/>. Figure created by the author.

Specific reasons for the coups

In Guinea, the decision of the former president, Alpha Condé, to change the constitution in order to be able to run for a third term in office was hugely unpopular. An Afrobarometer poll shows that eight out of ten Guineans preferred a two-term limit for the presidency. In Guinea, the junta’s justification for carrying out the coup was therefore more related to governance issues.

Mali has experienced two coup d’états within nine months. The first one was in August 2020, when President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita was ousted by the military led by Colonel Assimi Goïta. The coup came after three months of protests by Malians against irregularities in the parliamentary elections, while simultaneously demanding security, respect for democratic norms and the provision of basic services. The putschists named a transitional government, with Goïta serving as vice-president, and promised to hold elections in 18 months. Nine months after the first coup, Goïta seized power again from the interim president, Bah N’Daw, on 24 May 2021, accusing him and his administration of incompetence.

In Burkina Faso, the country’s citizens were frustrated with the civilian regime, which was accused of “corruption, laxity and nepotism”. According to the Institute for Security Studies, trust in government had been declining since 2017 due to lack of good governance.

Of all the recent coups in the Sahel region, the one in Niger was the most surprising. This is because the country was relatively politically stable, with a history of democracy spanning over a decade. In addition to the reasons given by the military junta that took power on 26 July, there are other issues that explain the coup, including the ethnicity of the president, the large number of foreign troops in the country, and the failure of regional organisations such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) to act against previous military takeovers.

Understanding the perceptions of citizens

While individual nations across Africa and around the world, together with organisations such as ECOWAS and the African Union (AU), have been united in condemning the military takeovers, large numbers of citizens in all four countries have taken part in demonstrations supporting the coups. Although the coups have not been universally accepted in all four countries, there have been considerable levels of support. This is because many people in these regions are not bothered about their countries’ form of government and only want governments that will deliver good governance, including security and a properly functioning economic system.

Two main factors explain the perceived support for military takeovers in these regions. The first is the increased spotlight on the corruption and lack of development in the countries experiencing the coups. This growing awareness results from better education and the increasingly widespread use of social media. An ever greater number of better educated young adults in particular are asking questions about how and by whom they are governed. Social media has made it easy for images and critiques to be circulated of rulers’ and their cronies’ wealth in the midst of the acute poverty of the majority of the countries’ peoples. Increased education has also made it easy for young people to understand the dynamics of their countries’ economies, especially in resource-rich countries. For instance, questions have been asked in Niger about how much the country is making in uranium sales and what is happening to the money. As long as democracy does not deliver positive dividends, more people are likely to support almost any alternative, including the military.

Secondly, the relationship with the former colonial power, France, had turned sour in the last decade. Although the crack in the relationship has been observed for quite a while, the advent of COVID-19 further strained the relationship. Developing countries – especially the least developed ones – felt abandoned by their supposed allies, in this case by France. Many citizens have argued that the strong relationship between their countries and France has not yielded any significant economic prosperity, and many citizens are demanding that their leaders switch to “other friendly” partners such as China and Russia. These issues are further compounded by the inability of France to contain Islamic insurrection in the wider region. All four countries where coups have occurred have been characterised by anti-France sentiments, and some of them have totally severed relations with the country, while Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger have expelled the French military forces based there.

Conclusion

The regions of West Africa and the Sahel are undergoing a period of political turbulence and democratic collapse. Organisations such as ECOWAS and the AU place a great deal of emphasis on the need for democratisation, but it is not enough to send election observers to monitor elections; the systems that support the emergence and sustainability of strong democracies must be strengthened, which is not the case. In addition, regional and continental organisations must take a strong stand against constitutional manipulations by incumbent presidents and ensure that democracies deliver dividends to the people. Steps must therefore be taken to help these four countries to return to democracy as soon as possible in order for these regions and the continent as a whole not to witness a contagion effect.