Latin America and transnational organised crime

Experts analyse the Biden-Putin Summit in Geneva

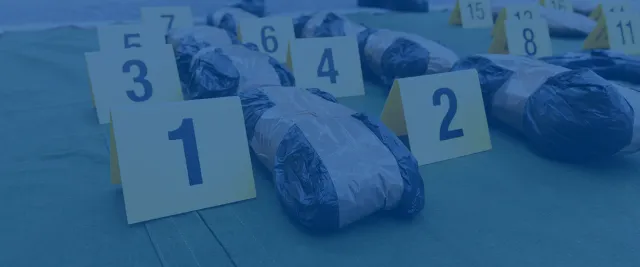

Dr Paul Vallet: Welcome to the Geneva Centre for Security Policy weekly podcast. I'm your host, Dr Paul Vallet, Associate Fellow with the Global Fellowship Initiative. For the next few weeks, I'm talking with subject matter experts to discuss issues of peace, security and international cooperation. Thank you, listeners for tuning in. As you may have heard, a successful law enforcement operation led worldwide by the US, European, Australian and New Zealand police forces has just concluded against international organised crime and drug trafficking networks, reminding us that the global importance of allied forces in fighting transnational crime. So, to discuss this I'm joined today by one of our guest speakers at this year's recently concluded Leadership in International Security Course, Professor Celina Realuyo. Professor Realuyo is Professor of Practice at the William J. Perry Center for Hemispheric Defense Studies at the National Defense University in the United States, where she focuses on US national security, illicit networks, transnational organised crime, counterterrorism, and threat finance issues in the Americas. She's a former US diplomat, also an international banker with Goldman Sachs, US counterterrorism official, and Professor of International Security Affairs at the National Defense Georgetown, George Washington, and Joint Special Operations Universities. Professor Realuyo has over two decades of experience in international public, private and academic sectors. She's a regular commentator in the international media, including CNN en Espanol, Deutsche Welle, Foreign Policy, Reuters and Univision and has testified before the US Congress on national security, terrorism and crime issues. Professor Realuyo is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, International Institute for Strategic Studies and women in international security. She has travelled to over 70 countries, she speaks English, French, Spanish, and is convergent in Italian, German, Filipino and Arabic. So, with all that combined knowledge, I think you will give us some fabulous insight into transnational crime. So welcome to the podcast, professor. And thank you for joining us today.

Professor Celina Realuyo: Thank you, Paul, for having me back.

Dr Paul Vallet: You're most welcome. My first question would be to, of course, set the scene. So, could you tell us what are the particularities of transnational crime? And do those particularities when applied to Latin America differ much from those of other regions?

Professor Celina Realuyo: to just take a look at the global perspective and your intro on that massive takedown using technology, and international cooperation of law enforcement and intelligence assets is a great publicised achievement to combat transnational organised crime. So we always wonder why does transnational organised crime exists? It's existed since the days of the Greeks and Romans as we think about contraband, slavery, all of the things that we have now are actually vestiges from ancient times. But what's different now with globalisation is with the technology, communications, and the global market. Sadly, for drugs, people, weapons, exotic animals, minerals, we've seen this explosion across the world. And these groups are most mostly motivated by one thing, maximising their profits, but also reducing their risk of getting caught by law enforcement agencies around the world. What we're seeing, though, as well is that in different parts of the world, they're different characteristics. So, you're located in Europe, that tends to be a destination country for these illicit trafficking issues, especially now for drugs. And the amount of cocaine arriving in Europe is tremendous as in the United States, we're less interested in consuming cocaine as opposed to opioids, which are synthetic drugs, we are seeing this massive flow that had traditionally gone from South America to North America towards European markets. So that's an example of how Europe is more of a destination or a consumer destination as opposed to the producers. So, in contrast, Latin America has predominantly been for the past 50 years, the main producers of obviously cocaine, but also trades in marijuana and heroin. And more recently, the advent of what we call synthetic drugs, such as opioids, particularly methamphetamine and fentanyl, that is impacting the United States tremendously. So just to give you a little context, as I am based in the US and I focus on the US, we sadly reached over 90,000 drug overdose deaths, mainly due to opioids, just last year and this was during the pandemic when the markets and points of sale had been closed. So Latin America is a producer, a transit and, more importantly, also now a consumer, which had not been the case in the past. So we're starting to see similarities across the world of the importance of reducing demand and even more importantly, socialising and educating the public at how dangerous these drugs especially combined with synthetics could be actually lethal.

Dr Paul Vallet: Well, that's already a sobering thought. And thank you, of course for highlighting the fact how Latin America interacts, in fact in with other regions in what is a global problem. So, that leads me to my second question, which is to wonder whether our Latin American authorities and Latin American solutions best suited to tackle the transnational crime in the region? Or would they require a more global dimension to the response to that crime with the input of other regions?

Professor Celina Realuyo: So, in Latin America, we've actually witnessed, unfortunately, many countries struggling to combat transnational organised crime and its different manifestations, right. So, we talk about drug trafficking, human smuggling, and trafficking arms and weapons trafficking and the money laundering that accompanies it. And, to their credit, many Latin American countries have established the legal frameworks in order to pursue particularly transnational criminal organisations, which means they can through Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties, and through sharing intelligence information, they've been able to collaborate particularly with us in the United States on massive operations. But the problem that you have is the issue of not just corruption, but weak institutions, even institutions that are infiltrated. And this is something that we've actually seen as an inherent challenge. But also the question is, how can other partner nations help the Latin American countries in their fight against transnational organised crime, and this is where we see a lot of help coming from Europe as well as the United States in terms of technical assistance and training to help build up the security forces, whether they be police or Gendarmerie, as well as trying to fortify their judicial systems, right? In order to actually bring the criminals to justice. And sadly, that's where we see a lot of high levels of impunity. Just to give you an example, in Mexico, only 3% of crimes are reported and brought to trial. So that leaves 97% in the case of impunity.

Dr Paul Vallet: Well, that's also pretty, pretty sobering. And, well, something that affects, of course, Latin America on that scale. But can you tell us how much does transnational crime in Latin America impact on the region's governance and when you're mentioning that, of course, and what it does to otherwise the region's potential contribution to global governance?

Professor Celina Realuyo: So this is actually the key issue that was touched upon by both President Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris, they've just embarked on a new initiative kind of trying to foster and more point promote anti-corruption problems through for US foreign assistance. And this perhaps, is the greatest challenge and if not the greatest threat, even more so than transnational crime is corruption. Why do I say that? So, corruption is not just an enabler of crime, but it's actually the product of crime. It's a crime in and of itself. So we even have talked about unfortunately, in certain parts of Latin America, certain parts of Mexico, Central America and Brazil, we speak about ungoverned spaces, where the governments are so weak or so corrupted, that the actual criminal groups and gangs and cartels are the ones that are providing basic government services. And we saw this during the pandemic, there are actually boxes of like little do it yourself, kits with food, vitamins masks hand sanitiser, with the logo of El Chapo Guzman, the head of the Sinaloa Cartel’s face imprinted on the box. So it was an example of how the cartel in this case, Sinaloa Cartel was trying to win the hearts and minds of the local population, who will be their accomplices as we come out of the pandemic and be more loyal to the cartel than to actually denounce cartel activities to the government. And we actually have sadly, the example of Venezuela under the Maduro regime, which is in its of itself claimed to be a mafia or actually a narco state. It's an example of how the Maduro and his associates use the monopoly of the use of violence and the armed security services to run an illicit economy. They survive through the illicit sale of oil, illegally mined gold, as well as the movement of tons of cocaine that are actually sadly destined to where you are Paul, in Europe. And we anticipate that as the economy starts to open up, and sadly too, as consumers are looking for that high, that new high, we're actually anticipating a spike in cocaine trafficking as international trade and flights and economies, because the point of sale has been aware that's been the chokehold as the quarantines are the curfews and the shutdowns that have been part of the COVID response policies, have actually impeded the distribution of drugs. And sadly too, we're seeing already that the levels of addiction because of the mental health issues associated with the lockdowns are starting to creep up. And that's why we're really worried about an explosion of not just of drug consumption, and to meet that drug consumption, massive amounts of illicit drug flows around the world, not just in certain regions, but it's something that we're anticipating will be a global wave.

Dr Paul Vallet: It's perhaps, difficult to say at this juncture, given what you've just explained to us, but if we're dreaming about bringing solutions to transnational crime in Latin America, do you think these solutions might be able to deliver what you've also alluded to, you know, quality improvements to the region's security and prosperity? But could that happen in a relatively short term, whether the solutions are implemented, or are they more likely to require a longer span of time to take effect?

Professor Celina Realuyo: So one of the most important tools that any government has is the use of its security forces to counter and combat very well armed and very well resourced transnational criminal organisations, so professionalizing, a country's military and police forces that respect the rule of law and human rights is essential for short term and long term. And we've seen several countries invest time, money and resources in trying to build those up. So, I just I spent a lot of time in Colombia and Mexico, I'm actually going to be in Mexico next month. And we've seen how they've even set up a new arm, which is called the National Guard, that is dealing with border security, but also trying to counter the cartels. What we've sadly seen, though, in the case of Mexico, as well, as more recently in Colombia, with the social protests, is, sadly a handful of those officers have committed human rights atrocities. And they need to be brought to justice in order to maintain the confidence of the population, that they're there to serve them and protect them and focus on what we call “citizen security.” Unfortunately, also, we've seen that there are cases of corruption within the armed forces and the police. And that's why still focused on what can be done in a societal level, to combat corruption, because everyone is a victim of corruption. So when we think about capital flight, or the illicit economy that creates distortions in market pricing, and what's very different in Latin America, compared to other parts of the world, is that the violence that is accompanying the drug trafficking and human trafficking is much higher than other parts of the world. And it's hard to explain, there are people who've tried to do it from a societal or cultural perspective, but they've gotten a lot of trouble for being politically correct. But just the homicide rates per 100,000 are extremely high in countries like Venezuela, Colombia, Jamaica, in the Caribbean, and in Mexico. And that's what we've seen that's very different than other parts of the world. And it's always this fight for the actual distribution and the roots, but also the money. And this is something that we're trying to understand how you can instil long term, enduring institutions that will be as respected as they have been in the past. So even during the pandemic, the military in most Latin American countries continues to be the most trusted institution followed by the Catholic Church, just to give you some perspective, but these are long term investments. And also you have to create and look at the next generation, who you select, how you train them, and most importantly, how you pay them, because that's what's happening is the cartels and the gangs are paying them more through bribes than the actual monthly salaries that they get.

Dr Paul Vallet: So I think definitely, perhaps more of a long term in order to make that an enduring one. My final question would be whether you think it's possible to envision a period in which Latin America might effectively break free of the grip of transnational crime, might it to do that before other regions?

Professor Celina Realuyo: It's difficult to see and I hate to be so pessimistic. But if I, through my research this past year, I actually posit that transnational criminal organisations in all parts of the world have actually been empowered by the pandemic. So why do I say that? What's interesting is that they were not impeded the way we anticipated that they would have been by the lock downs and the global paralysis of international trade. What they figured out was how to do workarounds, right? So they actually figured out in terms of from being the global criminal groups, they went local, like creating their own drug laboratories closer to home, so they can control the supply chain. The other thing is, too, we've actually seen rampant cases of corruption, where criminal organisations around the world are not just financing political campaigns, they're running their own candidates. So what is the antidote, I go back to the issue of rooting out corruption. So we've actually seen tremendous progress in international fora trying to a raise the issue of corruption, and then more importantly, invest in many, many more programs to fight corruption, and something that I specifically follow, which are illicit financial flows. So without the money, these groups cannot survive, and without corruption, they will not have the environment in which they can thrive. So this is a bigger question also of how? What is the antidote? The antidote is socio economic developments in licit and illicit economy in order to mitigate that temptation of being recruited. We speak a lot about youth at risk. And this is something that we're also very worried about as kind of one of the side effects of the pandemic, all these students who are not in school, looking for something to do that. Also, in desperation, they might be recruited by gangs and criminal organisations much more easily than they had been in the past. And this is something that is important as a call to action. At the societal level, many of us spent time watching Netflix and Amazon Prime in which the protagonists, we've actually seen, sadly, Hollywood glorifying transnational criminal networks, right? So if you think about the Narcos series in Netflix about the Colombian cartels, or Ben Affleck in The Accountant, that is actually a movie that also talks about how this person is just for the money, he was laundering money for terrorist groups and criminal organisations, and different mafias, or the series called Taken, I think you remember this, which is about human trafficking. And sadly, these are based on vignettes that are real, and we have to realise that it's not victimless. And I think there's been great strides made in terms of combating drug trafficking, we've been doing that for 50 years. But in more recent years, the scourge of human trafficking and modern slavery, and the money with the exposure of the Panama Papers, and most recently, the FinCEN files, we've seen a greater awareness. So, the bigger question is, what can government's do at the national level and at the multilateral level, in order to put all these well intentioned, anti-corruption and counter crime programs into practice? And that's what's going to be the challenge that we see in the post pandemic, with governments who are fiscally challenged because of the overhang of what we call the health and economic recovery that countries need at the national level? And then how can we foster international cooperation. So, there are ways to do it. And I still think a lot of it has to do with educating our young people right, to understand and not accept a political and national context filled with corruption. And that doesn't actually bring those who engage in corruption to justice. So, we're hopeful that I think the stark reality as we come out of the pandemic is going to show us opportunities, but we have to do it smarter. Because we anticipate there'll be actually less resources. And then technology, the bust that you explained at the opening of our session is a great example of how also technology is our friend, if we use it well, and we use it in collaboration with other law enforcement forces around the world, we can really make great strides. And remember, that's just one of the things that's been publicised. I assure our listeners that there are hardworking military intelligence and law enforcement agents around the world, working 24 hours a day to fight the scourge of transnational organised crime.

Dr Paul Vallet: Well, you've given us also a truly global spin to of course, the magnitude of this issue. And we can obviously, talk on many, many podcasts and shows that will perhaps have the occasion to do so more, but that's all we'll have time for today. So, I wish to thank you, Professor Celina Realuyo for your many thoughtful insights on this issue on today's programme. Thank you so much.

Professor Celina Realuyo: Thank you very much for having me.

Dr Paul Vallet: You're welcome to our listeners, as well, thank you for joining us. And please join us again next week to hear more about issues of peace, security and international cooperation. I'll remind you that you can follow us on Anchor FM and on Apple iTunes. You can subscribe also to us on Spotify and on SoundCloud. I'm Dr Paul Vallet with the Geneva Centre for Security Policy and until next time, bye for now.

Disclaimer: The views, information and opinions expressed in this digital product are the speakers’ own and do not necessarily reflect those shared by the Geneva Centre for Security Policy, its Foundation Council members or its employees. The GCSP is not responsible for and may not always verify the accuracy of the information contained in the digital products. Small editing differences occur between the audio and written transcript as well.

The GCSP also interviewed Professor Celina B. Realuyo, expert on transnational organised crime in Latin America. Interview available here.