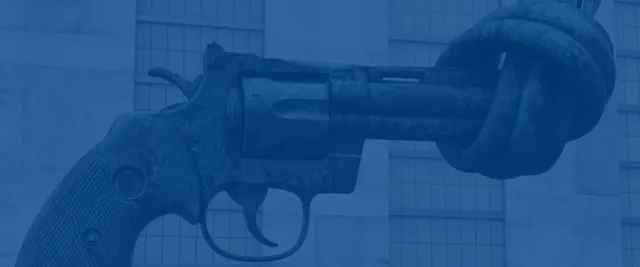

Creating the Arms Trade Treaty

Sustaining Peace: The Prevention of Human Rights Violations: Amb Yvette Stevens

The Geneva Centre for Security Policy podcast is your gateway to top conversations on international peace and security. It will bring you timely, relevant analysis from across the globe with over 1,000 multi-disciplinary experts speaking at 120 events and 80 courses every year. Click subscribe, download on your favourite podcast player, get notified each time we release our weekly episode.

Listen to Episode 28

Ms Ashley Müller: Welcome to the Geneva Centre for Security Policy Podcast. I’m Ashley Muller. This week’s episode explores some of the latest global issues affecting peace, security, and international cooperation.

Ms Ashley Müller: As the global arms trade continues to soar, efforts towards disarmament have become more urgent. We speak with Brian Wood, Manager of Arms Control, Security Trade and Human Rights with Amnesty International. We discuss the creation and evolution of the Arms Trade Treaty. Brian, you have worked with Amnesty International, a very important organisation dealing with human rights. So, how do you explain this relationship between human rights and the control of the arms trade?

Mr Brian Wood: Well, many years ago in the beginning of the 1980s, the Amnesty International movement passed a policy that they would oppose military, security, police arms transfers, as they called them, from one country to another, that contribute to serious violations of human rights. So that came from the worldwide members and it took some years for the legal department and the leaders of the movement to decide how to put that into practice in the organisation, because it’s an organisation that, you know, does evidence-based advocacy, so it had to put in place the research, and the policy and training in order to do that properly. And I was a member of staff from 1991 and I had come from Southern Africa, and in fact, I was very deeply involved in the anti-Apartheid movement there, working with the Namibians to try to get their independence, so I had come from that perspective, and I started working on this issue, initially on the transfer of equipment that’s used for torture and then that spread to work on Small Arms and Small Arms and Light Weapons, so I was at the beginning of the process where the United Nations began to set up a Programme of Action to Prevent the Illicit Trade in Small Arms and Light Weapons and so, soon after that, I met with a few non-governmental colleagues from small organisations at the Amnesty Headquarters and we decided that we would try to introduce the idea of a binding treaty, so what we did was, we thought we would start in the European Union, since the European Union already had some policy on that, and we received a bit of help from lawyers at universities in the UK. So, we floated a proposal and it found its way to Oscar Arias, the Nobel Prize winner and former President of Costa Rica and Don Oscar (as he is fondly called) called us to a meeting in the United States, along with some other Nobel Peace Laureates - as you know, Amnesty is a Nobel Peace Laureate - and we put more work into drafting this text and consulted lawyers again and we came up with a proposal called ‘Framework Convention on International Arms Transfers.’ So, Costa Rica floated that in the General Assembly and well, it didn’t receive much reaction, so we thought, ‘Okay, what we need to do is constructively engage in the capitals around the world and organise a multi-NGO campaign.’ So in 2003, Amnesty International and OxFam International and the International Action Network on Small Arms, which is lots of small NGOs, all got together and launched this campaign called ‘Control Arms’, and initially, we just had some support for the idea of an Arms Trade Treaty from some small countries, in addition to Costa Rica, it was Mozambique and I think Cambodia, in fact, countries that had been torn apart by the misuse of arms and the proliferation of arms. But, as it began to snowball and became a popular idea, some larger countries began to get involved and, for example, Finland, Ireland, the Netherlands, countries like that, Sweden. So we had these meetings in the UK, in Helsinki, and then Dar es Salam, a lot of African countries came, and soon after that, we had a breakthrough because the UK government decided that they would support the idea. Of course the details had to be settled and that was what started happening around about 2006-2007, meetings began to take place within the European Union, the idea was floated in the other regional organisations, and eventually six governments brought the resolution to the General Assembly and that was passed in 2010, it was agreed that we would have a negotiation within the United Nations. Of course, not all governments were on board, so there was initially a group of governmental experts that had to try and thrash out, you know, at least some of the detail. They reported back, and then it opened up in to what’s called an ‘Open-Ended Working Group’ at the United Nations, where all Member States can attend if they want. And so, from then on, there began to be a lot of ideas and input, and the Secretary-General invited States to put proposals, and so it, became the largest ever consultation that the United Nations had ever had on an issue. So by 2012, there were some serious deliberations and negotiations, some of the big powers were a bit sceptical, but once President Obama was elected into office, we began to get more support from the United States, which then brought a lot of other countries, after being cautious, brought them in. So the final negotiating conference in 2012, almost reached consensus, and then, the General Assembly had to reconvene the meeting in 2013 and finally, the General Assembly adopted the Treaty text, and that’s what we have today. So the civil society movement, which is very mixed, lots of different types of groups, peace groups, church groups, women’s groups, environmental, arms control groups, all sorts of different groups joined together and played actually a very big part in the process and will continue to do so, and people like myself try to encourage the colleagues in the non-governmental movement to be constructively engaged and to respect the right of States to self-defence and therefore to acquire the means of self-defence and their duty to protect their populations and enforce the law, so it’s not a movement that’s against the arms trade, it is a movement that wants a responsible arms trade, so within that understanding there is a lot of interactions, there is a lot of research that goes on, policy developments and mutual assistance in many parts of the world.

Ms Ashley Müller: Yes, and of course, the civil society organisations played a very active role in initiating the treaty, in negotiating the treaty and now they are recognised as a partner also in the implementation of the treaty: they are invited to the regular meetings of States Parties, here in Geneva. But sometimes you have the impression that there is some frustration because the States Parties, the governments seem to give more attention to the procedural aspects, the institutional aspects, the reporting, etc. They are not so much on what’s happening in reality, in conflict areas, where there is a lot of controversy about some exports to some countries in the Middle East which are actually used in conflict, and in fact on civilians. So we have this impression now, there is this frustration, this lack of dialogue about the actual implementation of the Treaty.

Mr Brian Wood: Well, yes, it’s true, there are strong debates, there are different points of view, governments have access to their own national security information and non-governmental organisations don’t. But the non-governmental organisations collate information from around the world, so sometimes, they’ve got something in addition to say and of course, it includes humanitarian aid organisations who are working on the ground and, you know, large human rights organisations who are working on the ground. So they are dealing with impact of armed conflict and the violations, sometimes the very serious violations or even crimes against humanity, on the ground. So they have that perspective they bring to the proceedings of the Conference of State Parties of the Arms Trade Treaty, which has several Working Groups, and you know, it’s still a very new process; the Treaty has got over a hundred States Parties in it, which is actually far more in a very short space of time [than for other treaties]. I remember, some very senior diplomats telling me that it would take 10 years for the Treaty to come into force, and actually it was less than two years that it was in force. There is quite a lot of momentum behind the Treaty, but there are not many states for example in the Asia region and the Middle East North Africa region. There is far more in Europe, the Americas and in significant parts of Africa, in Oceania. So, one of the considerations is that governments want to just go slowly, step by step, because they want States that have been, if you like, sitting on the fence, to come inside the house and get to know what the Treaty is all about. The other thing is that the terms of the Treaty are sometimes debateable in themselves, what do they mean? The Treaty doesn’t have definitions as such, so quite a lot of the provisions of the Treaty are interpreted from the definitions of other Treaties and other bodies of international law, so this is a big challenge, especially for the NGOs to learn the legal lexicon, if you like. The governments usually have their law offices, but even then, there’s a lot of different types of law that is within the Arms Trade Treaty umbrella, so International Humanitarian Law, International Human Rights Law, the law that falls under the United Nations Charter, there’s International Customary Law, International Criminal Law, Trade Law, and you know, Weapons Prohibitions, as well. So, there’s a lot of technical, legal and other technical issues that have to be worked through and limited amounts of time, limited amounts of money, so you know, we are seeing the birth of something that hopefully will become much bigger and more effective as time proceeds and it wouldn’t surprise me if the Conference of States Parties agrees some guidelines in order to assist States with interpreting it, there is a lot of work going on to help developing countries build capacity to implement the Treaty.

Ms Ashley Müller: And in that respect, you are a regular contributor to our training courses at GCSP and how do you assess the impact of this kind of training to improve the capacities of officials to implement the Treaty?

Mr Brian Wood: Well, I think what the Geneva Centre for Security Policy does in training officials on the Arms Trade Treaty issues is of a very high standard, I think it’s hugely beneficial; from having participated as a facilitator for some years now, and I have spoken with most of the participants over the years and they are extremely positive about the course and the materials, so I think this institute is doing a very fine job, it’s not the only one that’s doing capacity building training, but it’s certainly one of the leading places to come and learn about the Arms Trade Treaty.

Ms Ashley Müller: That's all we have now for today's episode. Thank you to Mr Brian Wood for joining us. Listen to us again next week to hear all the latest insights on international peace and security and don’t forget to subscribe to us on Apple iTunes, follow us on Spotify and SoundCloud. Bye for now.

More on Arms Proliferation at the GCSP

Disclaimer: The views, information and opinions expressed in this digital product are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect those shared by the Geneva Centre for Security Policy or its employees. The GCSP is not responsible for and may not always verify the accuracy of the information contained in the digital products.